Moving pictures

- Chris Rogers

- Dec 14, 2025

- 5 min read

Which is the more emotive, the still photograph or film footage? It’s hard to say. Your mother as a pigtailed girl, smiling cheekily, in a sepia snapshot; your son, scoring his first goal, in a shaky camcorder video. Both can have a profound impact when viewed. The motion picture depended on its motionless predecessor to exist and many films have of course featured photographs, but productions that blur the divide between the two intelligently and innovatively can generate real feeling.

The obvious, if literal, exemplar is French filmmaker Chris Marker’s famous short La Jetée (1962). A science fiction drama about an unnamed man whose obsessional memory of a childhood event may be the solution to world survival after a nuclear war, the work is composed almost entirely of still photographs with a voiceover the only narration. Though seemingly naïve, the choice of medium is appropriate given past, present and future are fundamental to the story whilst its interruption – seamlessly, breathtakingly – by a few seconds of motion picture footage demonstrates that real sophistication is at play.

A still image that briefly comes to life is also found in Ridley Scott’s futuristic film noir Blade Runner (1982), made twenty years later. This, too, has a startling effect but is merely the prologue to a far more elaborate iteration of the same idea found elsewhere in the story, namely when the jaded detective Deckard ‘enters’ a holographic photograph using a police computer terminal. He, and we, move between and around the person and the objects within that image on a hauntingly elegant yet enigmatic journey that climaxes in the discovery of a new character and a tantalising clue. Wholly cinematic, the multiply-referential (to Old Master paintings, real-world technology and Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon amongst others) sequence is also demonstrative as a knowledge base of visual techniques.

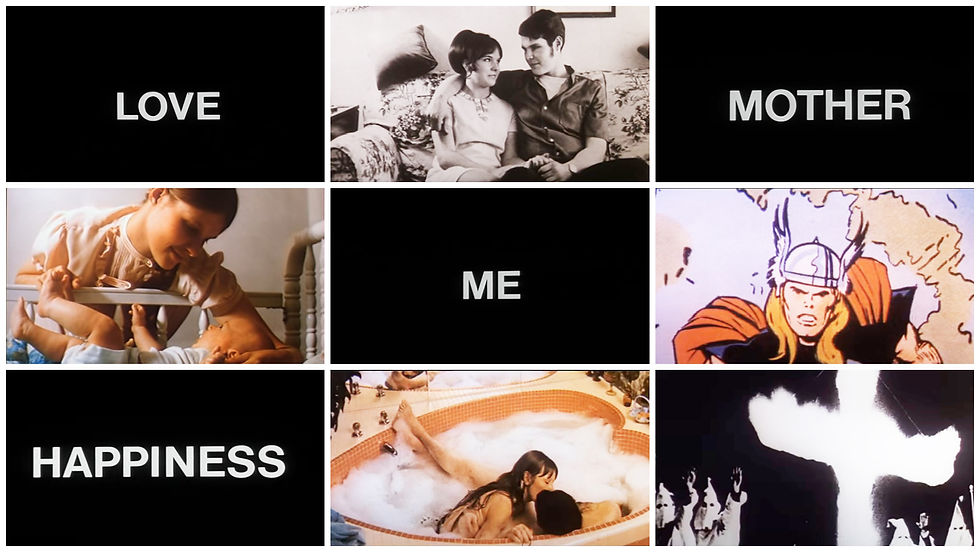

Manipulation of still images is also central to the arresting sequence at the heart of Alan J. Pakula’s conspiracy thriller The Parallax View (1974). Reporter Joe Frady, investigating a series of suspicious deaths and their links to a mysterious corporation, is invited to observe a montage of photographs whilst his reactions are monitored. At the outset, images of motherhood, youth, and apple pie America are reassuringly and recognisably categorised (by on-screen captions) but as the test progresses, those categories subtly shift and swap and so do the images they contain – ‘mother’ is sexualised, ‘country’ radicalised – as Frady is quietly assessed for his ability to act as killer, decoy or patsy. It is one of the most striking and disturbing scenes in US cinema and is no less effective for being an obvious reflection of the troubled times from which it emerged.

Diametrically opposite in tone, Robert Zemeckis's Back to the Future (1985) riffs on the grandfather paradox for its enjoyable journey ‘back in time’. As Marty McFly tries to stop his teenage mother falling in love with him and engineer a match with his to-be father instead, a photograph of his present whose subjects disappear and reappear acts as a visual warning of the consequences of failure.

It is unfortunate that director Michael Winner is not more widely recognised for his film The Mechanic (1972) and its remarkable 16-minute, dialogue-free opening. This sees assassin Charles Bronson meticulously planning a hit, beginning with surveillance of the target’s apartment. The monochrome photographs he has taken with a telephoto lens from the building opposite are shown full-screen, for several seconds each and in complete silence, as he pores over them. For tantalising minutes it is an extraordinary rejection of the ‘motion’ picture, whilst transporting the audience inside that apartment and making them complicit in the acts that follow.

A feature film that explores television, Michael Crichton’s Looker (1981) is a thriller about advertising models required to undergo unnecessary cosmetic surgery in a drive for perceived perfection. The emergence of computer-generated imagery is a key plot point, but a more intriguing technology also appears: a light gun whose victims ‘lose’ time when it is fired. A clever play on persistence of vision, the scientific concept that made movies possible, as well, perhaps, as a gently satirical comment on consumer behaviour, the conceit appeared just as audience members were getting used to being able to freeze-frame filmic action on their video cassette recorders.

Television itself has also taken on this intimate, adaptable relationship between photograph and film.

Written especially for the small screen, Stephen Poliakoff’s Shooting the Past (1999) champions the stories and memories captured by the older medium through the story of a stock library threatened with closure. To defend it, staff exploit their knowledge of the collection by selecting images and crafting from them very personal tales to persuade the new owner to relent. Powerful and affecting, these stories-within-a-story have a resonance outside of yet related to the narrative: real stock shots were employed as props but some were digitally altered to suit the needs of the story, whilst the source of those images – the famous Hulton Picture Library – had in fact been owned by the BBC before being sold a few years before the serial was made.

This year’s Netflix drama Eulogy, part of Charlie Brooker’s Black Mirror anthology series, takes this teasing out of memory and emotion from photographs to perhaps its highest level of execution yet, as a middle-aged man reluctantly tries to remember his lost love’s face by exploring, quite literally, the photographs he took of her that he later defaced. Paul Giamatti’s performance, often delivered to no other visible character, works its spell whilst carefully posed actors, extensive and complex stills photography and state-of-the-art computer-generated imagery provide the three-dimensionality that Giamatti walks through toward catharsis.

After so much angst, a more pleasurable final thought for the festive season.

The BBC’s landmark – and much-loved – adaptation of The Box of Delights (1984), first broadcast 41 Christmases ago, also has its characters entering a work of art – here a painting hanging on the wall of a room. Young Kay Harker is amazed as the mysterious Cole Hawlings escapes from danger by enlarging the painting to fill the room, stepping into it and mounting a donkey, which gently bears him to safety as the painting shrinks back to its normal size and position. The scene appears in John Masefield’s 1935 novel, which was published the year after P.L. Travers included the pavement art scene in her first Mary Poppins book.

It may not have been in the minds of either author that their ideas would one day be filmed, but at least the power of still images to construct and move us was recognised.

Comments