Dream machines: The sports car

The car industry may be in trouble, with sales down, marques changing hands like hot potatoes and environmental awareness increasingly forcing change, but around 60 million vehicles are still sold around the world each year, and every model those numbers represent has to be designed.

When intended for the volume market, even minor departures from the prevailing understanding of what constitutes an acceptable shape draw criticism. In Britain alone this was seen in 1982 with Ford’s then-radical Sierra, pejoratively nicknamed the jelly mould, and as late as 1995 with Vauxhall’s updated Vectra, thanks to its ‘daring’ door mirrors faired in to the body.

But the sports car is a wholly different affair.

Sold in far fewer numbers to a rather different customer base concerned with image and style as much as speed, the designer’s aim is to connote all three within a single form.

Where this succeeds, a feeling of beauty and of elegance is achieved. The car is a machine but also more than a machine; it transcends mere mechanics and becomes sculpture, totem, cultural icon. It is industrial design meeting art.

The post-war years confirmed the dedicated, specially-designed sports car as a crucial component of most motor manufacturers’ ranges. A world emerging from conflict saw such cars as representing the glamour and dreams of a previous era, evolving as they had from the modification and tuning of racing and touring cars during the first two decades of motoring’s existence. Earlier, too, were laid the roots of all car design. Because automobiles – horseless carriages, after all – evolved from horse-drawn vehicles, the terms used to describe them come directly from that older trade. ‘Coupé’, ‘cabriolet’ and ‘spider’, ‘running boards’, ‘hood’ and ‘trunk’; all originate in a craft whose very name is still used to describe the forming of a car’s bodywork: coachbuilding.

Now, the power and the glory could be available to all in a democratic, meritocratic future, and by the 1960s, nothing captured the spirit of the age like a sports car. Two exemplars that span that decade make this clear. Though from opposite sides of the world, their sensuous curves expressive of restrained energy reveal a shared design sensibility that epitomises the maturity of the designer’s work at this time.

Ferrari’s 250 GTO was designed by Sergio Scaglietti in 1962, and has been eminently desirable ever since. Far less well known is Toyota’s 2000GT, by Satoru Nozaki and dating from 1967. Properly grand tourers, giving sustained performance over distance, these gems nevertheless contain the essence of the classic post-war sports car. Both have deeply-curved, rear-set cockpits behind long, low bonnets, so low in the case of the Toyota that battery and air cleaner had to be fitted into compartments either side of the engine bay. Indeed, the Toyota’s ride height actually required the bottom edges of its doors to be curved upward to avoid them striking the ground when opened on a camber.

Both designs celebrated The Sixties and were perfectly matched to rising aspirations in west and east. As if to prove it, actor Sean Connery rode in a unique open-topped version of the 2000GT, custom-made for the production, in the Bond film You Only Live Twice.

British design talent was not absent from this market, of course. In 1961 Malcolm Sayer designed the E-type for Jaguar. Its recessed and faired headlights and chrome trim conveyed an air of tradition, belying its staggering power. Aston Martin’s DB5 arrived in 1963. Its styling, by Harold Beach, caught an earlier period but, tellingly, the car was depicted in the firm’s brochures arriving outside London’s defiantly modern (not to say Modernist) 28-storey Hilton hotel, opened the same year.

Sports car design since the 1960s has tended toward one of two schools: sharp angles, evoking a high-precision industrial past, or smooth curves, conjuring images of predatory, animalistic grace.

The first of these is a machine aesthetic, linking back to the engineering legacy that created the automobile and epitomised by the Swabia region of Germany, from which emerged Diesel, Daimler and Bosch and which has cradled Mercedes-Benz, Porsche and Maybach amongst other pioneers. A few years ago BMW sponsored an exhibition of work by alumni of the Bauhaus, explicitly linking car design to this industrial heritage.

It is this design movement that forged the Mercedes-Benz SLK in 1989. It is a tight, compact design composed of a bare minimum of elements, straight-edged and crisp. The whole recalls the clean, disciplined angles of the wartime Messerschmitt Me 109 fighter aircraft, also engineered for speed and manoeuvrability.

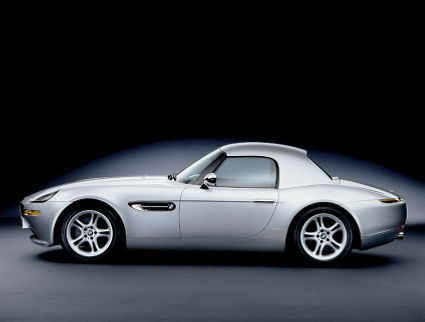

The second school is inspired unambiguously by those classic post-war designs such as the Ferrari and Toyota but also the 1954 Mercedes 300SL ‘Gullwing’ by Rudolf Uhlenhaut, reinvented today as that firm’s SLS, and the exceptionally beautiful Lamborghini Miura, which was styled in 1966 by Marcello Gandini and appeared in The Italian Job as shorthand for Italian style and in counterpoint to a trio of British Minis (in red, white and blue). BMW’s Z series of roadsters has followed this line and also consistently displayed the inheritance of its own marque. The curving, slightly cheeky, almost feminine bodywork of the Z8 from the turn of the millennium is a loving recreation of the legendary BMW 507 from half a century earlier. It also repeated the distinctive side vent, with chromed vanes and ingeniously-inset BMW roundel, of that model. The 2009 update of the Z4, designed by Dane Anders Warning two years later, also picks up this motif in a car whose complex side panels are a signature of the model; the original used a fold line to bisect the door-mounted roundel.

In 1995 Ford attempted to meld both approaches with its ‘New edge’ styling theme, which integrated angles and curves in a dynamic, agile manner. The scheme debuted with the GT90 concept car, modelled on the firm’s great GT40 racer. The Ford Puma sports car followed, as did the Ka and Focus for the mass market.

There is in fact a third broad shape type, one which enjoyed immense popularity for a short period before vanishing. The wedge was firmly a child of the seventies, born in 1974 with the outrageous Lamborghini Countach. An emphatically hard, masculine body shape with chunky slab sides and upward-swinging doors set the tone. Succinctly described by one contemporary British motoring magazine as “faster in Europe than a light aircraft”, the Countach, also designed by Gandini, popularised the term ‘supercar’ and was regarded with open-mouthed admiration by boys of all ages around the world. Stylistically, it took the link between car and aeronautical design to its logical next stage with the audacious use of NACA air inlet ducts, created by the American National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics in 1945 for cooling the engines of the first jet aircraft. Arriving as it did between the releases of 2001: A Space Odyssey in 1968 and Star Wars in 1977, a science fiction influence on the car’s design is also detectable. The Countach sowed a seed that flowered in subsequent models of the next decade or so, such as the BMW M1, the Aston Martin Bulldog and the Ferrari Testarossa.

Only in the last decade or so have these design trends begun to melt and flow into each other fully, reflecting changes in the wider world. Sports cars and grand tourers both benefited, as did coupes.

One of the most striking products of this approach was the Mercedes CLS of 2004, a four-door coupe with a beautiful side crease that moves in one graceful arc from the front wheel arch to the rear bumper, flawlessly integrating front wing, door and rear wing and forming a shape of real elegance. The Bentley Continental GT, designed by Belgian stylist Dirk van Braeckel, is built on Bentley owner Volkswagen’s mid-size frame shared across the group’s marques but its looks are its own. A taut, prowling pose with tight, muscular haunches brilliantly defines a car which, despite its size, is rendered sleek and fast and ready to pounce. Its rear, in particular, is highly effective.

Across all these forms, detailed design touches characteristic of the post-war golden age are used, whether scoops, scallops, vents or grilles. Maserati’s trademark triple side vents in an otherwise highly restrained, almost sober, body become a Savile Row tailor’s ticking, a subtle tip of the hat to the past.

With the SLK resembling the Me 109 and the E-type arguably echoing its opponent, the Supermarine Spitfire, it is not surprising to find similarities between cars and aircraft surfacing repeatedly in automobile promotion as well as design.

In advertising campaigns sports cars were and are frequently juxtaposed with airliners or jet fighters, conflating the two principal means of fast, luxurious, expensive travel of the twentieth century and also calling attention the closeness of design intent and outcome across both spheres.

This was made explicit in a 1990s television advert for Saab. A wholly conventional driver’s point-of-view shot, snaking along a twisting mountain pass, suddenly veers off the road and into thin air; cut to a Danish air force jet in flight and the tagline ‘Saab: the only aircraft manufacturer that also makes cars’.

The market has changed in other ways. Success is now no longer achievable through design alone, irrespective of actual performance. Such models fail, quietly in the case of the Triumph TR7 or Lotus Esprit, where smart looks were betrayed by poor mechanics, or spectacularly with the stainless steel-clad DeLorean DMC-12.

Increasing numbers of sports models are being designed, feeding demand but also subtracting somewhat from the inherent cache of the concept. A new Ferrari is a new Ferrari, but the exclusivity previously assumed by such a purchase surely reduces when a new model appears every couple of years. And aesthetically there is, in truth, little of the ‘wow’ factor about, say, Ferrari’s 458, despite its 202 mile-per-hour top speed. Jaguar has achieved acclaim for its 'X' range of cars, but their look is unoriginal and does nothing to set the heart racing, without even the compensation of convincing homage. Even Aston Martin’s DB9 seems staid.

And with the saloon and coupe envelope becoming a faster, more pragmatic and more attainable proposition for those in search of speed, there might be even less impetus for buyers to go all the way. Porsche now produces the Panamera, which looks like a 911 (in one’s rear-view mirror at least) and can reach 188 miles per hour but has four doors and seats four people – properly.

Meanwhile, niche makers such as McLaren or Pagani deploy expertise gained in specialist fields – Formula 1 racing and carbon fibre in their case – to extrude designs that are truly sporty, certainly, but which seem colder and more mechanical than the post-war classics. McLaren’s F1 has the purity of a machine tool but, like that object, lacks warmth and élan. It is not a design arising organically from a motoring heritage.

History will determine whether today’s models are treasured or even remembered in twenty years’ time. Future forms remain locked in the minds of designers not yet born. But it is likely that the sports car will remain a dream machine for some time yet.

___________________________________________________________________

Posted 28 January 2012

East meets west.: The Ferrari 250GTO... (diseno-art.com)

...and the Toyota 2000GT; note the side equipment hatch and upward-sloping door edges (alternatecars.blogspot.com)

"Achievement ahead: 300 SL type" The Mercedes SL ('Super Leicht') gullwing

Publicity for the BMW 507 capturing its engineering excellence and its glamour (desktopcar.net)

Its reincarnation as the Z8 (bimmerfile.com)

Bentley's Continental GT

Dream machine; the original Countach (pistonheads.com), and a follower - the Lancia Stratos