12 February 2021

Pre-sentence report

A formal planning application for the new City of London Law Courts complex, including the police block and commercial office, was lodged last month. Its documents confirm almost all of the conclusions I reached in my previous posts whilst adding detail; more on that below, but for now I’d like to focus on what to the vast majority of Londoners will be the most significant aspect of the scheme – does the principal building actually look like a court of law?

That is the same question that Eric Parry Architects addressed in October’s consultation by stating that their proposed design has "a substantial civic presence on Fleet Street”, something repeated in January’s application. I suspect most people would assess that claim by what the building looks like, and how it’s made – its massing, articulation and materials, in formal terms. But EPA make it clear that they are defining civic presence in two ways only, both of which are peripheral to the building’s architecture: “integrated public art commissions” and “a sense of place in the connections through the site”. This is a rather extraordinary approach and one somewhat at odds with history and precedent. It does, though, explain my earlier doubts about the court’s main façade, which neither conveys its function nor responds to the local context. Nothing in the application changes that.

Thus granite, limestone, the Royal arms and those of the City of London do not on their own a public building make, let alone a courthouse. There is little to indicate unambiguously the fact of the latter or to break up the bulk of what is a very large building; the slight “inflections” or chamfers to the corners of the plan are weak.

The public entrance on Fleet Street is described as being “clearly marked […] by the oriel window”, this last a reference to the facetted treatment of the elevation here that I divined before. That is technically correct, but the feature is rather shallow and reads more like a simple sub-division of the façade than a true oriel. Anticipating the separated circulations necessary within any court building, “A separate street entrance for Jury members and a separate entrance for the Judiciary have been provided” – their locations are redacted although elsewhere we are told that “The western façade to Whitefriars Street incorporates additional entrances at the ground floor for courthouse use.”

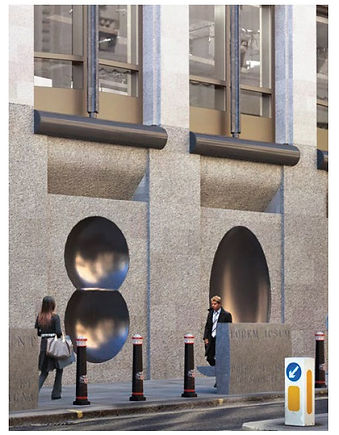

Other than the main doors no glazing is apparent to the ground floor at all, excused as necessary for security. One could see this as a nod to the Central Criminal Court nearby, yet given recent court buildings nationally have managed to include fenestration here it is disappointing that a better balance between architectural expression and safety could not have been managed in the capital. Instead we are to be treated merely to commissioned artworks incorporated into the wall panels, the explanation for those curious dish-shaped features I noted last year. Placed behind those panels at height will be hidden or “cryptoporticus” windows (the term, I discover, originated in ancient Greece to mean a covered corridor or passageway lit from openings at the tops of its supporting arches), to bring daylight into the lower levels of the building. These measures too have precedents in the City, though that does not mean they are welcome. At the former Unilever House (1932) the upper floors were pushed back to permit skylighting of the windowless ground floor, though car noise was the enemy there rather than car bombs, whilst the ‘blind’ street frontage of the GPO’s Fleet Building (1961) featured ceramic panels by Dorothy Annan. More art is suggested for the oriel, namely an expanse of stone suitable for incised text that might reflect “the ethos of the justice system or possibly the history of the area” and the possibility of overlaying the glazing with decorative metalwork or similar. This seems uninspired and, again, a poor replacement for actual architecture. It will be interesting to see if even these ideas are taken up – it was some years before Westminster magistrates’ court in Marylebone acquired its contemporary art installation, and a hundred of them for the National Gallery’s name to appear atop its portico.

We are forced to imagine the interior since not a single image of it appears anywhere in the application pack. The “feature” or “cantilevered high-quality” public staircase that I identified previously is the main element. Surprisingly reminiscent of that in the now-demolished Clements House (1957), a post-war office building in the City, right down to its position at the very rear of the floorplate where it is backlit by extensive glazing, it serves only the first four floors before a more conventional example takes over within the central, top-glazed lightwell. There are two more of the latter, all of them forming a sandwich with the service cores.

There will be eighteen courtrooms in total (eight crown, five magistrates Courts and five civil) though rather oddly “The exact location of these has been redacted on the plans for security purposes.” Ambitiously, daylighting will be provided on all four sides of each – the driver is wellbeing and this feat will be achieved through clerestory windows giving on to the exterior of the building, the public lobbies or those lightwells. Intriguingly, “open justice viewing areas” are promised, albeit with no explanation of what these might be. Those attractive boxed-out oriels to the south are consultation rooms for clients and lawyers. On the private side of the building, upper levels will contain “social rooms for the judicial [sic] and HMCTS administration staff with access to the garden terrace”; this outside amenity is for both to “de-stress, take some air and enjoy the views”.

Servicing will be from the shared basement primarily, which stretches across all three buildings. At its lowest level, basement 2, sits an energy centre that powers the courthouse and the police building assisted by plant situated on some upper storeys of the former. Above this, basement 1 holds fleet parking for rapid response police vehicles, who will exit (only, it appears) via their own ramp at the southern edge of the police building and for which traffic the local road layout will be adjusted. The “lower ground floor level” above that houses spaces associated with the courthouse including a cycle store, lockers and showers and a couple of parking bays for those with disabilities. Prisoners for hearings and police processing will also be received and despatched here via a custody area; cellular prison vans as well as delivery vehicles for all three buildings will use the same secure gate and ramp at the southern tip of the site, incorporated within the commercial block.

Returning to street level, as I predicted two years ago most of the courthouse will sit within a stockade of bollards. They will run up the northern end of Whitefriars Street, along Fleet Street (where they will be complemented by “stone sculptural elements which are either plaques for scripture or benching”; the road is part of the City ceremonial route) and continue along the turn into Salisbury Court. Here, the “new public green” offered in the July consultation that had, predictably, been downgraded into an expanse of hard landscaping dotted with planters by October remains, with a few tweaks to improve hostile vehicle mitigation. This is a pity as the current arrangement isn't perfect but at least feels like an actual London square. Baffling, though, is the word that could be applied to the continuing refusal to carry forward the existing pedestrian stepped link between the square and Primrose Hill to the south.

As for the rest of the scheme, the police building will, it is now clear, contain an operational station with a public counter as well as the City force’s headquarters; the open, glazed ground floor thus “promotes increased visibility and presence”. The greened area at street level, meanwhile, is revealed as a “wintergarden” enclosed by triple-glazed glass planks with small air gaps between them. The use of weathering steel, which I questioned last year, is now justified as expressing “institutional gravitas” but such a statement is illogical at best given the rarity and variety of the material’s use in Britain to date. Solemn reference to red enamel brises soleil recalling the old Ludgate railway bridge, absent almost a generation, merely prompts a bemused shake of the head. The commercial building covers its rational floorplates in a frenzy of terracotta, in reference to its neighbours, but is otherwise unremarkable.

This, then, is the scheme that will no doubt be approved in the spring; the window for comments has passed. It is unquestionably an important one, to the Square Mile, the capital and the criminal justice system. But whilst it may well evolve slightly as it is built out, I think that the awkward, bland and heavy design for the courthouse currently before us as well as the associated public realm represents an opportunity that has been missed, and by some distance at that.