Tower 42 today, with a revealing section below from a contemporary NatWest brochure

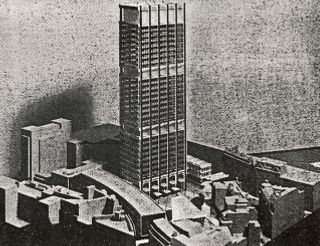

It began here, with the National Provincial’s 1964 plan, top (in model form, as published in The Financial Times). A few years later, the scheme had evolved into a single super-tall tower or, as shown here in The Times in 1970, a shorter main tower with a secondary building adjacent

Distorted by a wide-angle lens, this image of the tower at opening is taken from Bishopsgate. It shows the new City branch of the NatWest tucked behind Gibson's building, with the highwalk to its right, before a bridge across Bishopsgate was installed

Tower 42

A decade into the 21st century, with a second generation of super-tall towers built, under construction or planned in the City of London, it can be hard to appreciate the shock of height.

As post-war austerity eased, the late 1950s and early 1960s saw the first sproutings in a forest of tall buildings in the capital as a whole, amongst them the Hilton Hotel and Knightsbridge barracks, the Post Office Tower and New Zealand House. The City was not left out, with London Wall rebuilt along Modernist, Corbusian lines producing a rigid grid of six towers of nearly equal height, and a wide range of individual blocks going up, including the acclaimed Commercial Union and P&O towers.

All of these, though tall, were rectilinear Mies-inspired boxes; calm, cool, rational… and perhaps rather dull. More interesting were the shaped variety, such as the three triangular residential towers of the Barbican estate by Chamberlin, Powell & Bon and the chunky seven-sided Stock Exchange by Llewelyn Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker & Bor, executive architects Fitzroy Robinson & Partners and Joseph, F. Milton Cashmore & Partners. By adopting other geometric plans and highly modelled façades, exciting forms were created that became sculptural objects in their own right.

The greatest of this generation was Richard Seifert’s NatWest Tower. Its 600 foot (183 metre) height, embracing 52 storeys, striking plan and state of the art technology became a totem for the City, the tallest building in the whole of London until Cesar Pelli’s One Canada Square overtook it in 1990 and the tallest in the Square Mile itself for an astonishing 30 years.

The story begins, appropriately enough, with spectacular growth in another field; joint stock banking. After 19th century legislation allowed these companies to form, economic expansion and mergers followed. Three major names emerged: the National Provincial, the District and the Westminster.

After World War 2, government restrictions were relaxed, competition from foreign firms increased and mechanisation developed at an increasing rate. The largest British banks grew their operations accordingly, with new services such as cheque and cash cards and new financial products. As the 60s started to swing even the staid City yielded to fashion with the Westminster bank rebuilding its site in Lombard Street, spiritual home of the industry, with a new branch complete with porte cochere for drive-in banking.

A final regulatory relaxation led to the inevitable, and in January 1970 the National Westminster Bank was created from the three firms mentioned. Even whilst the merger was being mooted, it was clear the nascent bank would require a new base. The question was where.

The new institution found itself occupying a wide range of buildings inherited from its constituent parts. These included the magnificent inter-war palace of the Westminster at 41 Lothbury by Mewès & Davis and John Gibson’s sumptuous Romanesque 15 Bishopsgate of 1865 for National Provincial, with its double-height banking hall behind giant-order columns and arched windows. In 1964, the National Provincial had planned a single 450-foot tower in Old Broad Street, enabled by demolition of Philip Hardwick’s City of London Club there and 15 Bishopsgate. The then London County Council, planning authority for the capital, objected. A public inquiry followed, the outcome of which – rather in line with the contemporaneous failure of Peter Palumbo’s Mansion House proposal designed by Mies Van der Rohe himself – was approval of the plans but a confirmation of the listing of 15 Bishopsgate. This halted the scheme and the National Provincial chose instead to lease Richard Seifert’s speculatively-built Drapers Gardens tower. Adapted for their use mid-way through design and construction, it become the National Provincial’s head office on completion in 1967.

The National Provincial still harboured a desire to build on the Old Broad Street site, however, and as the merger progressed, the earlier application was revived. Plans for various new schemes were worked up by Richard Seifert and exhibited in the summer of 1969.

By early 1970 and the merger, these had crystallised into a single 600 foot tower standing in a public piazza, trading openness and permeability for height. It also brought more natural light to the lower levels of the tower and permitted neighbouring buildings to retain their rights of light, and would be a suitable home for the new National Westminster Bank.

After objections to this great height – almost twice that of St Paul’s – an alternative was prepared in which the height was reduced to 500 feet with the accommodation so lost moved to a smaller, 184 foot building next door. This would have shrunk the pizza, and occupying two buildings would have complicated operations. As such the single tower was the option preferred by NatWest, the Royal Fine Arts Commission and the Corporation of London, who felt it would become the focal point of a cluster of super-tall towers in this part of the City. That concept has been prevalent – and controversial – in City planning ever since. Gibson’s 15 Bishopsgate would be retained in both schemes.

Importantly, detailed models for these schemes showed that the profile of the main tower had already been fixed whichever was chosen. It was a distinctive outline which, in its taller iteration, would go on to make the tower an immediate symbol of the City and an architectural icon, before that term commonly applied.

In plan three wings, called leaves and shaped like part-hexagons with rounded corners, are wrapped around a central core of similar shape and cantilevered out from it by 30 feet. In elevation, the base of each successive leaf starts at a level two floors higher than the last when moving clockwise around the core from Old Broad Street, although at the tops the leaves actually step down by the same amount, moving in the same direction. The leaves are thus of different heights, descending in size around the core.

With the polyhedral shape reducing bulk, the result is a silhouette of real and surprising subtlety. The extreme height of the tower was emphasised by the exterior finish. Windows were bronze-tinted and closely set, divided by exaggerated mullions that formed continuous vertical ribs rising the full height of each leaf. Sheet stainless steel cladding for these mullions caught the light and further eased the eye up the tower, whilst the exposed top of the core is also treated with vertical ribbing to elongate the building.

The similarity of the new tower’s plan to the logo of its owner, much debated even today, was remarked upon at the time. Interviewed in the contemporary press, Seifert staff denied a link and pointed instead to the complexities of fitting a square, space-efficient building plan into a roughly triangular site.

Planning permission for the 600 foot tower was granted in May 1970. In construction and operation, it featured extensive use of high technology. In the public eye, this combined with the startling design to produce an elegant building that fully achieved its role as a focal point for the City at the start of the 1980s.

Construction did not actually begin until 1971 and took nine years. The engineering required to realise the design – the building was the tallest cantilevered structure in the world – was considerable. A concrete raft resting on deep piles supported a basement extending more than 50 feet below ground and containing car parking and delivery access. In-situ casting of the concrete core featured an early use of lasers to ensure correct alignment, and closed-circuit television cameras assisted tower crane operators.

Although the core’s purpose was principally structural, as anchor for the cantilevered leaves, it also housed the tower’s services. Thus within its perimeter behind the office space were escape stairs and toilets, and at its heart were three banks of four lifts forming a triangle. One provided an express service to the upper floors. American-style sky lobbies on the 23rd and 24th floor functioned as interchange levels for these and there were five double-deck lifts, each car of which only served odd or even floors. One acted as a combined executive and goods lift. Plant was housed in three intermediate floors interspersed between the office levels, along with roof-top boilers and air conditioning equipment.

Innovation could be seen throughout the new building, including gas turbine stand-by generators, a mechanical document delivery system and automated ‘robot’ window washing rigs. Air conditioning, lighting, security and lift operations were computerised.

The top four storeys contained a viewing gallery, corporate hospitality suite and kitchens, and no fewer than three entrance levels were provided, at the podium, via a mezzanine and from the street.

This was principally a legacy of the Corporation’s ill-fated elevated ‘ped-way’ or highwalk scheme of the early 1960s. Never very successful even on its own terms, it had been limited by designation of the first conservation areas in 1971 and 1974 and radically cut to a minimum desired network in 1976. The NatWest tower was therefore one of the last major buildings to be required to integrate itself into a system which had effectively been abandoned by the time it opened. It is ironic, then, that the sinuous, spiralling walkways connecting the building to the ped-way system are much grander in scope, shape and finish here than anywhere else in the City, and that the multi-level entrances that resulted make much more sense in a building blessed with double-deck lifts.

Though the most prominent, the tower was not the only element of the redevelopment scheme. Two much smaller office structures flanked the main entrance on Old Broad Street to the west, whilst to the east a four-storey block at 21-23 Bishopsgate formed the new flagship City branch of the NatWest. It was built immediately adjacent to the Victorian Gibson building, which was restored and used for conferences. A link block joined the Gibson hall to the new Old Broad Street buildings, acting as an ante room for the former. A surviving garden built around Fountain Court was retained. Although 21-23 Bishopsgate’s interiors attempted to provide some late-70s glamour, both these annexes were rather nondescript, with polished stone cladding and flush glazing; a calm setting in which to show off the dynamic tower.

The NatWest tower was completed and in use by April 1980, but received its Royal opening only in July 1981, weeks before that year’s Royal wedding. This seems appropriate, with the tower, a rocket ship ready to blast off to financial heaven, symbolising another aspect of a landmark decade and remaining the tallest building in the capital for the whole of it.

But despite its undoubted prestige, the NatWest tower was a compromise. It was never large enough to house all of the new bank’s operations and became a base only for its international banking division. The awkward shape of the leaves reduced flexibility, and the core-and-cantilever concept restricted the size of the office floors – and still not all are column-free. Just six years after it opened, the revolution that was Big Bang transformed the architectural needs of many financial services firms and drove them to demand massive open trading floors, impossible in a tower. The group headquarters settled at 41 Lothbury and remained there until NatWest was taken over by RBS in 2000.